Okavango Delta – a river system that drains not into sea, but into desert. With the seasonal rains of Angola come a deluge of water that creates a lush swamp in seemingly lifeless dry flats in Botswana. This attracts animals from all over southern Africa, where life is constantly on the move in search of the resources amid scarcity. There are few figures more rare than an apex predator, a bellwether of depleted lands. In the last fifty years, Africa’s population of lions has dwindled from 450,000 to less than 20,000. Encroachment by man, destruction of habitat, and eradication of the herbivores that lions eat or the plants the herbivores eat has set up the iconic lion for the last stage before extinction.

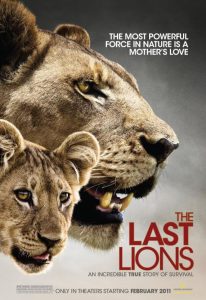

We have heard this many times before, and have collectively paid little heed to it. Whether this matters to you will not affect how you will feel about The Last Lions. Dereck Joubert has crafted an immaculately shot and well-constructed story about a lioness cast out of her hunting lands. The cinematography is almost distractingly beautiful(particularly the night camerawork), but what sets this feature apart is the strength of its narrative, drawing you in. Some nature documentaries make the mistake of anthropomorphizing their subjects. The Last Lions dwells upon what a lion may be thinking or feeling, but rarely stretches for meaning – they are animals, as we are, and share similar drives.

As the story opens, the lioness is under attack, and is driven from its hunting grounds. A disaster for a territorial animal, this is especially dangerous for the three vulnerable cubs that are her charge. Over half of all cubs die before reaching an age where they can hunt. The lion pride that has attacked her was in turn pushed south by human encroachment and guns. She flees to the south, into a watery land that is alien to a lion, since they despise water. The river is dangerous, brimming with crocodiles and hippos; even the marsh island beyond is filled with peril.

Though hooved mammals are a source of food for the lioness, she must hunt Cape Buffalo here. This herd numbers over fifty, and the sharp horns and dense build could mean a fatal wound. The dominant bull is disfigured with a white scar, and his ability to muster his herd to defend itself places the lioness in a difficult position. In a strange land, she must learn to hunt lethal prey. Adapt or die, in Africa as elsewhere. Against this challenge she must guard her young and defend her ground against the lion pride that drove her from her homeland. The plot unfolds naturally from the well-edited material. There are no villains or protagonists here; the lioness must provide for her cubs, while the buffalo adults fight to protect their calves; drama lacking in malice can be the most moving, as it is more relevant to our experience in a world of gray.

The camerawork attains an intimacy with the lions and buffalo, close enough to catch nuances in behavior. The lioness charges the herd, only to be met by the scarred bull. Attacking a calf on the flank of the herd results in a brisk response, and she is nearly surrounded. Eventually, she attempts the water, a tactic known for lions, but exceedingly rare. The water provides near-perfect cover for her hunts. This trial-and-error is captured in a series of scenes that effectively conveys the strategies involved in adaptation. And the errors are numerous for this mother – when tragedy strikes, her behavior becomes erratic, then dangerous.

Joubert manages to film an extraordinary event: the lioness attacks a one-ton bull buffalo in front of the entire herd. Despite the lack of human characters, the event is harrowing to watch, and it is difficult to avoid feeling a howl of rage emitting silently from the stricken mother. This is not anthropomorphizing – this is observation. And the lioness, covered in blood that is only partially hers, charges again and again. I watch a lot of wildlife features, and this is superior edge-of seat drama.

As The Last Lions approaches a climax, we see melodrama worthy of Sirk as the lioness experiences something lost, and everything gained. This is but one narrative in a continent filled with them, and expertly told by Joubert. The cinematography blends grand vistas of the African veldt with personal moments of the lioness experiencing bonding, the concentration of hunting, and the pain of grief. Remarkable images are caught on camera, such as a lioness in repose in a dead tree, silhouetted against the purple sunset; stalking the herd while moving silently through fog. This must have been a difficult film to make, but Dereck Joubert’s experience with National Geographic and his knowledge of Botswana gives an effortless appearance. The narration by Jeremy Irons does underline some behavioral observations about the subjects of the film, but it would play just as well in total silence. The images presented here lay the foundation for a powerful narrative, and this makes The Last Lions one of the strongest films of the year so far.

As the voiceover closes on The Last Lions, Irons dispassionately wonders if these shall indeed be the last lions on earth. Dereck and Beverly Joubert are anything but dispassionate. Go to www.causeanuproar.org to read more about the disappearing lions and other cat species across the globe. I will not even argue that this is a moral imperative. Preserving the wild places and ensuring the future of wildlife is a conservative measure – changing as little as possible about the world upon which we depend is how we can ensure our survival as a species. We have demonstrated before how poorly we understand the effect we have on our world.