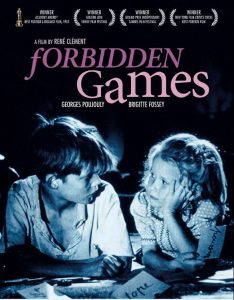

Given my utter disdain for all things “youth” — innocence, purity, possibility, young people themselves — it would seem impossible that I would openly embrace a film about children, but Rene Clement’s 1952 classic Forbidden Games is a notable exception. Its singularity of purpose and clarity of narrative (and shocking lack of cheap sentimentality) bring it beyond the scope of two children, then, and make it a lasting document about war, death, and the corruption of man. Taking place in France, circa 1940, just as the Nazi juggernaut is sweeping across Europe, the story considers the sad life of Paulette, a 5-year-old girl who loses both parents and a dog while ducking an air raid. She wanders about for a time until she is discovered by Michel, a young lad who lives on a farm with his family. Paulette is taken on by the clan, and while she is embraced as an unfortunate cost of war, her primary connection is with Michel.

As a glimpse of family life during the Nazi invasion, Forbidden Games is stark, quiet, and unfailingly authentic, but after the initial aerial assault, we never again she the weapons of war. Instead, Paulette and Michel deal with their situation by creating a graveyard for dead creatures they have found lying about. However, wanting to fill the cemetery to capacity, Michel starts killing chicks, cockroaches, and other small creatures in the area. Paulette even suggests that more people are needed. Each time, a hole is dug, the body tossed in, and the children proceed with the holy rites of a religious burial (including erecting makeshift, and eventually stolen, crosses). Sure, it sounds “sweet” and “adorable,” but this film is far too smart to cater to such obvious ploys.

True, the events speak to a naïve understanding of life and death and how an orphaned girl deals with a devastating loss she couldn’t possibly understand, but it is also clear that by mindlessly imitating the rituals of adults, they bring forth a far more powerful theme — that adults, seemingly intelligent and hardened by experience, are as incapable of dealing with death as children. We appear to grieve and assess our emotions, but in fact substitute empty tradition for any real understanding. After all, no child on earth would ever know about God, or Jesus, or the concept of prayer unless instructed by a “superior” grownup. And yet, we continue to believe that repeating certain phrases or wearing certain garments bring us a sophistication and maturity that would be dismissed as “play” during childhood. It’s all fantasy, yet we don’t have the excuse of underdeveloped brains to fall back on.

Quite a bit hinges on the secret graveyard, the stolen crosses, and a rivalry between neighbors, but such things are not nearly as important as the relationship between Paulette and Michel. The story ends badly for them, as it must, and yet we realize — some, quite reluctantly — that life, far from being “progressive” or an advance through stages of improvement, is little more than brief snippets of joy that serve only to interrupt, but not prevent, the loss and emptiness that define our experience. All that we are, then, is how we manage in the face of death. Paulette and Michel’s behavior, far from macabre or twisted, is the ultimate preparation for what lies ahead. Let Michel’s eventual disposal of the cache of crosses speak to us all — dead is dead, and gone is gone, no matter the size of our memorial.