Anyone who frequents Ruthless knows that Miranda July, the laughably untalented performance artist who gave birth to cinemas most offensive creation of the year, Me and You and Everyone We Know, sent me scrambling to the thesaurus to discover new and previously unused synonyms for that which fosters fevered, demented fantasies of ritualized torture. And my brief flirtation with voodoo did not in fact liquefy Miranda’s organs or guarantee that if and when she allowed the dreaded phallus to penetrate her oppressed vagina to begin a new life, that same creation would be sent tumbling from her stink chest in a righteous display of miscarried justice. And so she lives, no doubt continuing to create for those who long ago learned it is best not to cross a madwoman who refers to menstruation as a purification rite.

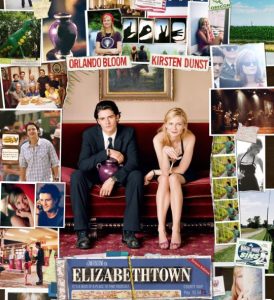

Fortunately, director Cameron Crowe has seen fit to provide a new target for my undying rage; an image of the silver screen so heinous and deplorable that it’ almost as if Mr. Crowe knew exactly what it would take to distract me from my murderous pursuit of Ms. July. She is Claire Colburn, portrayed by Kirsten Dunst, and beyond the shifting Southern accent, wafer-thin frame that betrays the inner bulimic, and remarkable ability to appear at a moments’ notice (or whenever the screenplay requires it), she is that sort of woman — unique to the films of recent years, it seems — who never, ever, ever shuts the fuck up. She effortlessly radiates the absurdities of her gender: childish instinct, feeling, and the winds of the moment that trump the cool reason of civilization and responsible living.

She offers advice, spouts personal philosophy, slips in bon mots and other words to the wise, and is so gosh-darn life-affirming and delightful that the only reasonable fate for such a person is the third act introduction of a time machine, a hastily arranged kidnapping, a sex change, a circumcision and a swift deposit into the bowels of Auschwitz, where the gurgling screams of this blond nightmare would be no match for my jackal-like guffaws. And depending on my mood, she wasn’t even the worst thing about Elizabethtown.

Elizabethtown is simply beyond description; a film so ill-conceived, bumbling, and incoherent that had it not been for the astounding moronitude of Claire, or the wretched, pained acting of uber-hunk Orlando Bloom, I would have left within ten minutes, but when things are this bad, I am compelled to stick around, if only because I might need something to round out my worst of the year list. But more than slipping in near the end, I have every confidence that this gaping wound of a picture will challenge for the coveted top spot, although under penalty of the rack I don’t believe I could ever dislodge July’s back-alley abortion. It’s not only the umpteenth exploration of the road trip (please, someone, write a script where a man learns about himself while sitting on his fucking toilet), but one of the most brutal accounts yet of that old chestnut: the sad sack who is redeemed by the quirky outsider.

You know, the kind of woman he’s never met before, or who has a special talent like knowing how to assess people simply by their names. Those people who wear funky red hats, or who create elaborate scavenger hunts just so that they can appear amidst a crowd with a child-like smile and goofy wave. A woman so beyond the pale that she invents boyfriends to confuse you, and who can, like, talk on her cell for hours and hours, even while playing CDs, painting her nails in the bathtub, or throwing out lines like, “let’s share a beer over the phone.” A free-spirit type so kind and sweet and wonderful that she single-handedly reinforces my belief that nothing is sexier than dripping misanthropy. Expressions of hope, then, are the surest road to impotence.

Back to Mr. Bloom (as Drew Baylor) for a moment, if I may. He is a shoe designer who has just created the biggest bomb in the history of the industry; a mistake which will cost his company $972 million. We don’t ever learn why the shoe is such a disaster, although in a few brief shots, it is revealed to be quite unattractive. Depressed beyond belief, Drew goes home, deposits the contents of his apartment by the curb, and returns to commit suicide. But rather than take his own life like any normal human being would, Drew decides to attach a knife to his exercise machine and create a death trap so complex that Wile E. Coyote himself would be impressed.

But had Drew not built this crazy contraption, he would not have had the time to stay alive just long enough to receive a phone call from his sister telling him that his father has died suddenly of a heart attack. Having seen more than three movies in my life, I know that this death will trigger the old “return to the past,” which means that city boy Drew will have to travel to a small town, deal with the expected eccentrics, and leave a better man. I’m not sure if these clichés are the result of standardized film schools, shitty writers or if in fact most people lead the same dreary lives. Either way, the viewer is made to suffer for an artist’s inability to think independently or take genuine risks.

Drew returns to Elizabethtown, Kentucky to retrieve his father’s body, as well as visit with kinfolk he hasn’t seen in years. But before he arrives, he meets Claire on the plane, for she is the flight attendant on perhaps the only airline in existence that would charge up a jumbo jet for two lonely passengers. Perhaps there are such flights, but the whole thing smacked like yet another meet-cute, for how else would Drew find sweet little Claire? He’s the quiet type, which is exactly what someone like Claire prefers, as an actual dialogue might complicate her suffocating narcissism. She claims she is addicted to helping people, which might seem selfless and kind, but in fact it is an egomaniacs way of always feeling necessary. Claire has to fix every problem because otherwise, she’d drive everyone in her vicinity to suicide. More than merely irritating, though, she’s one of the least authentic characters I’ve ever seen — and I’ve seen a few — as she utters tripe that could only have come from a screenwriter who’s trying desperately to sound clever. Someone, somewhere might speak this way, or view the world in this manner, but she’s likely studying to be an actress, not serving peanuts to weary businessmen.

Drew finally arrives at his destination, where he is met by a mutton-chopped cousin who chirps, “Your pain will be met by a hurricane of love.” Of course he does. It’s not every cracker who sounds like your average guest on Oprah. And we know that Drew’s father was an earthy, huggable man, because the entire town is silent in tribute. Signs hang in hardware store windows, the entire American Legion has seen fit to pay a visit, and the home of Drew’ uncle is literally teeming with relatives, friends, and neighbors. You see, Drew has lived an empty life until now, chasing money and fame, while forgetting that what gives meaning to existence is family.

This sentiment is supposed to hold firm, despite the fact that the house is engulfed by the deafening roar of children, old busybodies, and endless bouts of cooking. And how, exactly, is this tornado more fulfilling than fat paychecks? It takes scenes like these to remind me that the bonds of blood guarantee little but obligatory gatherings with people you would normally cross the street to avoid. Between the pinched cheeks, spoonful’s of the latest sauce, or harassing questions, there are precious few gunshots. I’d feel bad for Drew having to endure this mess, but Bloom’s inability to convey even the faintest hint of emotion throws him in with the rest of the mental ward. Were he to exchange places with his father, it would require great concentration to notice the difference.

And so Drew continues on, debating the clan about burial versus cremation, the fact that the family actually lived in Oregon and not California, and trying to deal with a wedding party staying at his hotel. The fellow guests are a comic lowlight, never more so than when Drew meets up with the groom-to-be, reveals the details about his fathers’ death, and is forced to endure bear-like hugs and the sort of hysterical sobbing found nowhere in real life. Drew’s mother Hollie (Susan Sarandon) even comes out for the memorial service, for no other reason than to embarrass the hell out of a once proud actress. Hollie, you see, has been on the move since her husband’s death, which means that she’s learning how to cook, taking tap dancing lessons, and learning how to laugh for the first time. All of this also means that she’ll perform one or more of these new talents at the service, much to the delight of the crowd and the simultaneous horror of yours truly. But as bad as Hollie’s soft-shoe to “Moon River” is, it fails to match the burning papier mâché bird that assaults the audience while a cover band wades through Lynyrd Skynyrd’s Freebird. Funny? Farcical? Wacky? An emphatic no on all counts. I haven’t been that flushed since I shat forth my last Big Mac. Needless to say, the funeral itself features the old malfunctioning casket gag, which wasn’t enough to produce a slight grin the other 335 times I saw it.

The film ends with a perfunctory road trip, all at the insistence of the demonic Claire. She hands him a box for the journey, which contains dozens of compilation CDs, obsessively detailed maps, and hours of recorded instructions about what to see and how to see it. This should have been the final clue as to Claire’s mental state, but he plays along and actually follows everything to the letter. He plays all of Claire’s (or Crowe’s) favorite classic tunes, talks to the urn containing his father, stops here and there spreading ashes, and annoys us even further with painfully stilted line readings.

These scenes were, strangely enough, the only ones that could be endured, as he visits some great destinations that made me feel like taking a trip of my own. Had the soundtrack played and Claire’s annoying narration been shut off, I might have smiled. Instead, I had to listen to someone of Claire’s warped perspective describe the site of Martin Luther King’s assassination while U2 thundered in the background, or hear her grating cadence wax poetic about the tree at the site of the Oklahoma City bombing. Funny how that which should be powerful and affecting is transformed into hollow kitsch depending on who’s sharing the moment. It’s like having Pamela Anderson conduct a tour at Gettysburg.

Simply put, this film is a colossal bore; slammed together in a shit sandwich with unappealing characters, dimwitted story turns, and so much unnecessary music that one is tempted never to listen to the radio again. It’s an iron rule that if a scene isn’t strong enough on its own, a piece of pop music needs to be inserted so we know how to feel. Crowe, perhaps channeling his revoltingly sunny disposition into Claire’s character, would make an ideal motivational speaker, as the only answers one needs in the face of death, depression, and despair are to be found on an Elton John record. Failing that, consult your garden variety psychopath, so long as she knows how to kiss and looks pretty good in a dress. For an anorexic.