Paul Newman’s glorious cinematic career was brought to an end by a machine gun-toting Tom Hanks.

“I’m glad it’s you,” he says to his imminent murderer during the rain-soaked finale of Road to Perdition.

Of course, this sort of far-fetched rubbish (patiently waiting to be gunned down before paying a compliment to your assassin) can only happen in the movies. Still, I’m not going to let such a tiny misstep at the end of a near-half century in front of the camera deter me from declaring Newman one of the most stellar actors of all time.

With his winning smile, sheer star power and undisputed acting chops, this guy was the real deal.

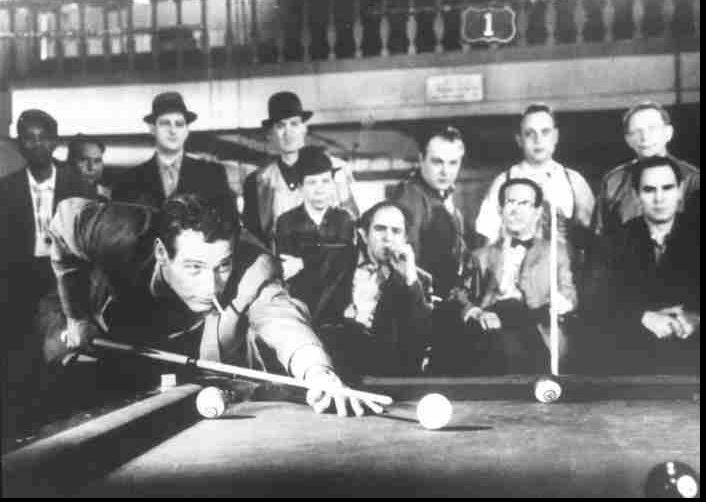

The Hustler (1961)

Accusations can sting, especially if you suspect somewhere in the back of your mind they’re true, so try dealing with being called a born loser.

Pool shark Fast Eddie Felson spends most of this chilly black and white classic wondering if Bert Gordon’s (George C. Scott) withering assessment carries any weight.

It just doesn’t make sense to this cocky guy. How can anyone say such a goddamn stupid thing? After all, Eddie’s as handsome as Elvis, he’s got the smarts and talent to burn.

“I’m the best there ever is,” he tells his alcoholic girlfriend, Sarah (Piper Laurie). “All of a sudden I got oil in my arm. The pool cue’s part of me, you know? It’s got nerves in it. It’s a piece of wood, but it’s got nerves in it. You feel the roll of those balls. You don’t have to look, you just know, and I can make shots nobody’s ever made before.”

Not only that, but Gordon’s ‘loser’ verdict is delivered while he’s more than ten grand ahead in a marathon duel with the country’s best player, Minnesota Fats (Jackie Gleason).

Soon afterward Eddie crumbles and drunkenly collapses on the floor with his self-belief (and maybe his soul) in tatters.

And so why did he lose?

Because he has no character.

Or as his judgmental tormentor Gordon points out while rubbing salt into the wound: “Minnesota Fats has more character in his little finger than you got in your whole skinny body.”

The rest of the movie centers on Eddie’s search for character while exploring the none too straightforward nature of winning and losing.

The thirty-six-year-old Newman was already a star by the time he took on the iconic role of Fast Eddie Felson, but I’d say this was the first pic in which he fulfilled his potential. He really is very good here, obviously comfortable with a cue in his hands, and aided by the smooth direction and lean, knowing dialogue. I’d love to tell you he owns every scene but although it’s Eddie’s story, he gets fierce competition from the three other leads. Laurie, Gleason, and especially the sinister Scott (whose poisonous mentality lingers over everything like stale pool hall smoke) are outstanding as well.

Hud (1963)

The man with the barbed wire soul! so, the tagline proclaimed, although the slightly less poetic The man who’s a right selfish shit would’ve also done the job.

Newman was never the sort of actor to play a serial killer, but he was more than capable of turning his hand to arrogant, unpleasant bastards, such as this seriously disgruntled cowboy.

Within ten minutes we get a firm grasp of his character.

Or rather, his lack of it.

“I always say the law was meant to be interpreted in a lenient manner,” he says with a twinkle in his voice. “Sometimes I lean to one side of it, sometimes I lean to the other…”

Hud drinks, fights, cuckolds the local men, is out for himself and will walk over anyone who gets in his way, including family. He’ll even park his open-top Cadillac on your flower patch.

“If you don’t look out for yourself, the only helping hand you’ll get is when they lower the box,” he tells his admiring seventeen-year-old nephew, Lonnie (Brandon deWilde).

He also possesses an entitled attitude to women. Or as the ranch’s sassy housekeeper (Patricia Neal) complains when he drunkenly puts his arms around her and kisses her neck: “Don’t you ever ask?”

This sour, self-centered behavior has long brought him into conflict with his honorable, principled father, Homer (Melvyn Douglas). “You don’t value nothing, you don’t respect nothing, you don’t keep no check on your appetites at all,” Homer tells his estranged son. “You live just for yourself and that makes you not fit to live with.”

But their relationship’s inevitable implosion is nothing next to the ominous discovery of a dead heifer. Disaster is just around the corner. Hud, of course, wants to offload the infected cattle (“Let’s put our bread in that gravy while it’s still hot”) before the government has a chance to declare foot-and-mouth disease. Homer, however, is not the sort of guy to go in for such dirty tricks.

From here it’s just a question of whether Lonnie is going to follow in Hud’s footsteps or his beloved grandfather’s.

Hud is a superb, elegiac western that contains a number of piercing scenes, such as Hud’s wordless, attempted rape of the housekeeper and the ghastly, Nazi-like destruction of the ranch’s livestock. You know it’s well-written, well-acted stuff because the decent characters (the nephew, the housekeeper and especially the father) are every bit as compelling as that ‘cold-blooded bastard’ Hud.

Cool Hand Luke (1967)

One thing I’ve never understood about this masterpiece is how someone can end up in prison for two years (on a bloody chain gang) because of drunkenly knocking the heads off a few parking meters. Seems a bit draconian, especially as the guy’s a decorated war hero. Here in Oz we’d just force such a harmless nitwit to have a mullet haircut and attend at least ten games of Australian Rules Football. Surely that’s a more fitting punishment?

That’s pretty much the only criticism I can make of Cool Hand, though, coz it’s a triumph otherwise. During the first half hour, Luke doesn’t say much but he’s obviously a taciturn loner with a chip or two on his shoulder. Gradually we get a handle on his code, best summed up when he says: “A man’s gotta go his own way.”

He’s an individual then, a man who’s none too enamored by rules, bosses, kowtowing and routine.

But it’s more than that. Much, much more.

Now some men are stubborn, but Luke’s refusal to stay down during his outdoor boxing match with his bigger fellow inmate Dragline (George Kennedy) suggests a deeper problem. Time and time again he’s knocked off his feet but he keeps coming back. In fact, his inability to concede defeat is masochistic to the point of mental disorder. The disquieting incident stands as a microcosm for his nature: bloodied and defeated, yet still standing and groggily looking for the fight long after everyone else has grown weary, if not sickened, by his actions.

The movie’s celebrated egg-eating sequence is another example of his impulsive, dogged nature, a feat achieved without the slightest thought for his health (“I never planned anything in my life.”) He won’t be beaten by any man, let alone by a major intake of heart-clogging cholesterol. Then once his digestion has been given the workout of its life he stands outside in an electrical storm as everyone else runs for cover.

“Ain’t ya scared of dying?” Dragline asks.

“Dying?” he replies, before staring at the furious sky and indulging in one of his periodic God-taunting sessions. “Boy, he can have this little life anytime he wants to.”

However, Luke’s renowned obstinacy is one of the keys to his popularity and influence. This is a man who’s alive, who won’t kiss anyone’s ass nor let the system break him. Most of his fellow convicts see him as an ‘original’ and a ‘natural born world shaker’, but not all are convinced. “Luke’s got more guts than brains,” one observes.

The prison warden, memorably played by the diminutive, potbellied Strother Martin, offers an even blunter assessment. “Some men you just can’t reach… A man needs to get his mind right.”

In some ways the warden, who smells ‘rabbit’ in Luke’s blood, is right. He’s an unimaginative, vaguely sadistic clot, but it’s obvious that the feckless way Luke is going about things isn’t helping anyone, least of all himself. The man’s a screw-up. Handsome, intelligent, charismatic and all the rest, sure, but still a screw-up. Luke does need to get his mind right.

And on top of all that, he may have a death wish.

How else can his macho, poisonous battle of wills with the system ultimately be explained? Just like McMurphy in Cuckoo’s Nest and Rambo in First Blood, there’s no way he can win. His thrashing around is merely a pointless expenditure of energy in which focus is placed on the wrong things. As a result, precious time gets lost.

However, it’s the standout scene with his cancer-stricken mother where we truly understand Luke’s a loser. Even though the guard won’t allow any contact, he also butts heads here, but in a gentler, much more poignant way. She reveals how a wayward husband has resulted in a similarly wayward son, although she can’t help loving him more than his estranged brother. It hasn’t been an easy road for her to travel.

“You know sometimes, I wish people was like dogs,” she says. “Comes a time, a day like, when the bitch just don’t recognize the pups no more so she don’t have no love nor hopes to give her pain. She just don’t give a damn.” After a pronounced coughing fit, she looks at him and says: “Luke… What went wrong?”

“You done yer best,” is all he can say, barely able to look at her. “A man’s gotta go his own way.”

And that’s why Luke is not a man to be admired, his demented refusal to bow before The Man resulting in him being unable to hold his much-loved dying mother nor attend her funeral.

The amazing trick here though is Newman puts in such a magnetic tour de force performance that he almost manages to patch over Luke’s gaping deficiencies.

Almost.

The Towering Inferno (1974)

I recently read something about 9/11 which said the people caught up in the overwhelming horror inside the Twin Towers conducted themselves in an orderly manner, apparently keen to help one another get to safety. I’ve no idea if that’s accurate, but I have to say I prefer movie truth when it comes to disasters. You know, hysterical women, arrogant or incompetent authority figures, and self-centered scumbags tossing children, nuns and the severely wounded over their shoulders as they sprint for the emergency exits.

The Towering Inferno features these tropes to a certain degree, but I’d still argue it’s several cuts above most disaster pics. It ended up as the biggest hit of 1974, its gigantic $200 million success resulting in a thirst for catastrophe that has since seen mankind threatened by killer African bees, suicide-inducing trees, and rollercoaster trains flying off the tracks into busy hotdog stands.

However, Inferno is a long way from such silliness because its setup (the world’s tallest building catching fire thanks to some dodgy electrical wiring) is worryingly plausible.

Newman plays the duped architect who thought he’d designed a perfectly safe skyscraper. It’s a fairly undemanding role for such a class actor and he’s not integral to the movie’s success, but at least there’s a bit of dick swinging with fire chief Steve McQueen. Catch the elevator scene in which they appear to be trying to telepathically communicate I’m the bigger star before McQueen tetchily observes: “Now you know there’s no sure way for us to fight a fire on anything over the seventh floor, but you guys just keep building ’em as high as you can.”

Newman almost sticks his chest out. “You here to take me on or the fire?”

At almost three hours long and very much a star-studded, old-fashioned Hollywood extravaganza, Inferno remains a surprisingly tense and inventive watch. It has excellent special effects, some unsettling set pieces (such as the hastily rigged up, overloaded breeches buoy plummeting to the ground), and a memorably watery climax.

Of course, I could do without groan-worthy stuff like Newman rescuing a couple of annoyingly fire-proof children, but there’s much to take pleasure in, such as Robert Wagner wrapping a damp towel around his head and boasting to a recently banged secretary that the burning room he needs to cross is no problem. “I used to run the hundred in ten flat,” he tells her before bursting into flame about four seconds later.

Slap Shot (1977)

“Everyone’s on their feet screaming ‘Kill! Kill! Kill!’ This is hockey!”

So bawls a fired-up radio commentator and it’s a fair indication of how this riotous flick unfolds, reveling in the sporting aggro while attempting a half-assed condemnation of how the modern game has developed.

But mainly reveling in it.

Newman is Reggie Dunlop, the aging player-coach of a failing team in a failing town. As he skates onto the rink, he’s greeted with cries such as: “Dunlop, you stink!”

Then he gets landed with the Hanson Brothers, three bespectacled psychotic goons who are introduced beating up a vending machine.

“Those guys are retards,” is his initial verdict, a perfectly reasonable observation that’s only reinforced when he finally lets them loose on the ice. Mayhem follows (even their teammates call them a ‘fucking disgrace’) but the previously hostile fans are won over, attendances start increasing and the team goes on a hot winning streak.

What we’ve got here is a failure to play by the rules.

Suddenly reinvigorated, Reggie begins encouraging the rest of the team to do anything they can to get the psychological edge, such as taunting an opposition goalie about his bisexual wife. “You gotta twist ’em,” he insists, “fuck with them.”

Now while I don’t think this world-weary George Roy Hill movie with its very funny mass mooning bus scene and convincingly staged action is about anything at all, it’s deservedly become a cult classic. Anyone who’s into R-rated comedies, such as 48 Hrs., should like it.

Newman’s not really known for his comedic performances but he’s terrific here, at ease with both the hockey stick in his hands and the relentless profanity. Mind you, he’s gleefully upstaged by the Hansons who are coldcocking an opponent one moment before holding an uncooperative hotel manager upside down the next.

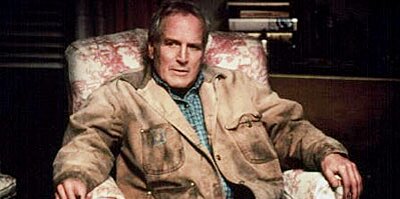

The Verdict (1982)

The courtroom drama is hardly my favorite subgenre (coz, you know, not enough tits) but The Verdict is simply a magnificent piece of cinema.

Its success is down to many factors, such as its fantastic script, topnotch acting and ability to lob in surprises, but what I appreciate most is the way it so nimbly manages to sidestep cliches.

Alcoholic lawyer Frank Galvin (Newman) is leading a washed-up life that involves melancholy games of pinball, bad food, the DTs, very little work and widow-bothering fishing trips inside funeral homes. There are plenty of long gazes into space as if he’s trying to see any kind of a future at all.

Then his one remaining mate Mickey (Jack Warden) chucks him a medical negligence case after doctors at a Catholic hospital tried to deliver a baby, but ended up killing the unborn child and putting its mum into a coma.

All Frank needs to do is settle out of court to enjoy a nice, easy payday.

He’s ready to play ball, but things change when he visits the hospital ward to take Polaroids of the unresponsive victim. Frank’s workmanlike expression slowly changes as he begins to appreciate the enormity of her plight, leading him to sit, put the camera away and listen to the steady hiss of the ventilator that pointlessly keeps her alive. As a nurse bustles in to tell him he needs to leave, he replies “I’m her attorney” and, for the first time, you know he means it.

But redemptive fights for justice are never straightforward, especially when you’re taking on a powerful institution like the repellent, ass-covering Church and its wealthy, privileged doctors. Frank is offered $210,000, a sum that appears to be the price of his soul.

“If I take the money, I’m lost,” he says. “I’d just be a rich ambulance chaser.”

Suddenly he’s locked into a grim, underhanded battle with the defendants’ legal team, a bunch of well-heeled, smug sharks led by Ed Concannon (James Mason), memorably described at one point as the ‘Prince of fucking Darkness’.

There are no missteps at all in this wonderfully nuanced David and Goliath tale. Every scene quietly builds on the previous one while it’s not often you get to see Newman spark a woman out.

Deservedly Oscar-nominated, but losing out to a little bald chap playing Gandhi, I’d argue this was Newman’s last great movie. Still, there was plenty of success to come, culminating in a gold statuette for taking on the role of Fast Eddie Felson once again.

“Hey,” he says at the end of the very good The Color of Money, “I’m back!”

And somehow I doubt Paul Newman will ever go away.