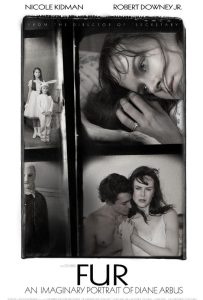

Given his bizarre life and equally unpredictable career, I had to expect that one day Robert Downey Jr. would play Chewbacca, although I hardly anticipated the role being featured in a quirky love story about famed photographer Diane Arbus (played by Nicole Kidman). Downey is Lionel, a wolf man of sorts, though it would be more accurate to say heÂs a dog-faced boy all grown up, who is now living in a New York City apartment right above Ms. Arbus. She had yet to gain celebrity when we first meet her, and she is little more than an assistant to her talented yet slightly dull husband, while also the specimen under glass for her well-to-do parents. She is decidedly of the era; clean, respectable, decent, and of course, dreadfully mediocre. Who knew that sheÂd ever encounter a man literally covered in fur, and that that same individual would be the inspiration she had been looking for?

Downey as Sasquatch is, of course, ridiculous on its face, and he had me giggling from the word “go” (I doubt I’ll see a more bizarre performance all year). He’s at his most ludicrous when dressed to the nines in a suit and tie, offering Diane a cookie while gingerly sipping tea. In many ways, the movie has no business ever recovering from this turn of events, especially when we are so accustomed to the conventional tricks of biographical storytelling. We are supposed to witness a childhood, subsequent trauma, trial by fire, and the beginnings of the genius we all now take for granted. The arc is so obvious and expected that every year, Hollywood churns them out like sausage in order to receive the expected Oscar nominations.

We all love a true story, and never more so than when they play by the rules. Fur, on the other hand, dispenses with the rules at the outset, announcing that the events to follow are not historical biography, and that the tale is an imaginary retelling that seeks not absolute truth, but hopes to resonate just as deeply. Needless to say, this revelation, while admirable in its honesty, scared the living hell out of me, as I had visions of performance artists rushing to and fro, drinking menstrual blood, and slamming daggers into assorted images of overbearing fathers and weak, bourbon-sipping mothers. I had no idea how wrong I’d be.

Instead, we do not get the Arbus of legend, nor do we get a straight shot from her photographs to the obligatory suicide in 1971, but rather a conscious fabrication; a sketch of emotions and shadings that attempts to explain what turned an Eisenhower dullard into America’s most celebrated champion of freaks, weirdos, and fringe oddities (such as midgets, armless chicks, nudists, and cross-dressers). Diane is first stunned, then fascinated by, and eventually attracted to Lionel, perhaps because he is everything her family is not, and more to the point, because he is her ticket to the only real freedom she has ever known; a relationship without judgment, pettiness, or the typical grumblings of mainstream couplings.

Sure, this relationship likely never existed in Diane’s actual life, but I admire the courage of the filmmaker to suggest that something of this sort was the initial spark for a full decade of revolutionary portraits. If we are left to wonder, as we often are in the world of celebrity, why not take an enormous risk and invite outrage and disgust? Sure, the movie is a bit overlong and may have taken one left turn too many (did it require an extended, full-body shaving sequence?), but at its core, it celebrates everything I have come to love about film festivals, especially Telluride. Take what you know, challenge it, turn it on its head, and churn out something wholly unrelated to what you’re likely to see in a given week. More than that, I’m not interested in a Diane Arbus that lived as all artists must; I’d rather look deeper, and have the art be in the telling as well.