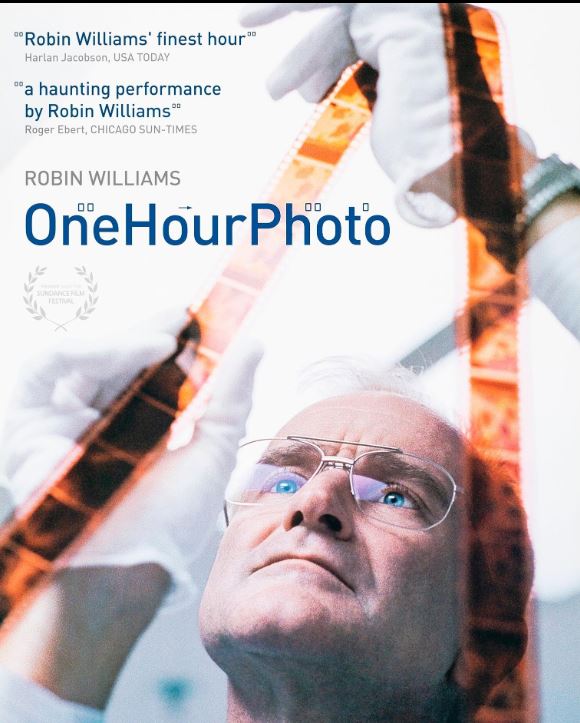

After years of shameless mugging and sappy sentimentality, it appears that Robin Williams has finally found the courage to be unlikable. Instead of pleading for our love and using all forms of manipulation to extract tears and sympathy, he has taken a great risk with the character Sy Parrish, a man as far away from Patch Adams or Jakob the Liar as one could get.

One Hour Photo, then, is a welcome departure because it forces Williams to use dramatic subtlety rather than the usual tired shtick that has made him an object of scorn for audiences and critics alike. One hopes that he will maintain an affinity for these challenging roles, but given the depressing reality that only a few scripts a year are even worth the paper they are printed on, the joy found here will be, alas, short-lived.

Parrish, a lonely “photo guy” working at a large retail store, captures our attention because he is so obviously troubled, yet we are unable to ascertain the source of his pain. He works tirelessly at his job, obsessing over prints, color balance, and the various machines that govern his life. He is outwardly attentive to his customers, although it is apparent that his gestures are a bit too involved for some. His place of employment is of a stark white sterility, stripped of emotion and any semblance of the “authentic life.”

Perhaps it is an obvious touch that the Wal-Marts of the world have become breeding grounds for manufactured joy and mindless consumer-driven conformity, but it is somehow fitting that Parrish would prefer to inhabit an environment without the hues and touches of the outside world. When we follow Parrish back to his apartment, we witness a similar scene – living quarters that resemble a prison cell rather than a lived-in domain. Watching television without any discernable reaction and eating dinner with all the gusto of a nauseous cancer patient, Parrish lives to develop the photographs that have come to act as a substitute for his own existence.

In a telling voiceover, Parrish tells us that there is much to be learned from the photos that people bring to be developed. From the elderly woman who brings in nothing but snapshots of her cats, to the amateur porn artist, Sy observes from a privileged position by which the personal and private become revelations of character. And, as he informs us, it is curious indeed that photographs tell a particular story, for these shots are almost always of events that bring us joy – birthdays, weddings, births, honeymoons. “No one takes pictures of things we want to forget,” he says. Therefore, it stands to reason that Sy, or anyone for that matter, could easily idealize the life of another from these photos. If the family we have come to “know” via photographs is all smiles, love, and togetherness, we are apt to believe that similar behaviors are the rule when the camera is tucked away. Only the most naÃve (or disturbed, as in Sy’s case) would believe that families can, or must, be this perfect, but that is the film’s strongest thematic point, and the primary reason to enjoy the film.

Early on (and as a result of the voiceovers and fantasy sequences), I took Sy to be a self-described moral guardian – a William Bennett-style arbiter of the public’s taste and values. Through his narrow lens, he has come to romanticize the American family (specifically, the Yorkin clan) to such an extent that all of us must adhere to a rigid set of rules and regulations or face judgment at best, exacting retribution at worst. In Sy’s world (and the world of all those who preach “family values” ad nauseam), mom and dad are plucky bundles of endless love, preparing peanut butter and jelly sandwiches, reading bedtime stories, and always, always ready to offer smiles, encouragement, and words of wisdom.

Children are healthy, precocious, and well-adjusted, with problems that never seem to exceed getting caught for chewing gum in class. Sy knows that he only sees a partial record of these lives, yet he desperately needs to believe that the images in his head are living, breathing realities.

Sy’s world begins to crumble when his obsession interferes with his usually honorable work ethic. Gazing deeply at the family photos of the Yorkin brood, he spends too much time at lunch and snaps at other workers. Moreover, his surreptitious thievery of photos (he makes himself a personal set whenever he develops the Yorkin’s pictures) has come to the attention of his unsympathetic boss. With his world crumbling around him (Sy is a man who can relate to Willy Loman’s sense of “job-as-identity”), he becomes even more insistent on his need for the perfect family, including efforts that seek to “punish” the wrongdoers who threaten that harmony.

Without revealing the particulars, let it be said that Sy does not move in a predictable direction and despite an atmosphere that would suggest impending violence, it is not Sy’s desire to kill, only “correct.” He wants to humiliate and expose, if only to show that any betrayal of the American Ideal will not stand. Once again, I take you to Mr. Bennett – he and his kind are not murderers (not yet), but they have a clear agenda with an even clearer sense of what constitutes the “penalty phase” for those people (adulterers, homosexuals, pro-choice activists, liberals, the non-goose stepping) who have different notions of family.

The final fifteen minutes or so are, sadly, a departure from the slow burn that defines so much of One Hour Photo, but such a direction is not a fatal one. While the stale cliche of a chase and the obligatory psycho-babble substituting for character depth hurt the film’s chances of being near-perfect, Williams’ performance remains a testament to grace and nuance. He rarely cracks and when he does, it is to the proper degree and never overstated. Therefore, he is menacing and mysterious, until of course we find out “why” his obsession has taken root (no hints, but c’mon, what else could it be?) I am impatient with such simplistic reasoning, for it is much more powerful to state that a man, otherwise reasonable, can hold others to ridiculous standards of decency and righteousness.

Does someone who is passionate about an issue or idea need to be mentally unsound, even “crazy?” How infinitely more frightening it must be to know that in our world, there are respectable sorts – rational, loving, and even-tempered – who have the capacity to commit heinous acts. In other words, let the movies reflect the troubling reality that judgment – pure, naked, sanctimonious rage – is as mainstream and yes, American, as the family ideal held by so many.

Again, One Hour Photo is a good film, perhaps flirting with greatness, because it creates an atmosphere of foreboding that is genuinely palpable. The performances are uniformly excellent and the direction quite lively, without ever resorting to the stylistic tricks so common to the first-timer. And, until that end sequence, the film stimulated interesting thoughts regarding obsession and the danger of ideal types. I did not want yet another example of the “crazy-man-stalks-a-family” genre and for the most part, I was pleased to have my wishes fulfilled.

Sy is a logical extension of the family values crowd, consumed as they are with running the lives of others, and it was refreshing to see such issues tackled in an adult, frank manner. But, as is all too common, the filmmakers lost their nerve in the end, perhaps reluctant to indict an entire culture when a lone individual proved sufficient. For them, Sy is just a man rather than the Everyman he needs to be.

Leave a Reply