Watching (or should I say enduring) Big Fish is like spending two hours with that obnoxious drunk at the end of the bar who simply won’t shut the fuck up. Like that grating old coot, the hero of Big Fish, one Edward Bloom (played by Ewan McGregor and Albert Finney), yammers endlessly about utter nonsense that could interest only himself, yet smiles and winks in the expectation that you’ll be as fascinated as he is. The crux of the story involves Edward’s son Will (Billy Crudup), who comes to see the old man after he falls ill. Will brings his pregnant bride from Paris and he vows to set things straight with his estranged papa. But before I get to that, I must address the brief Paris scenes. In the span of two minutes, we get two of the oldest (and most irritating) clichés in all of cinema. First, Will’s office has a view of the Eiffel Tower. Second, the bag his wife brings home from the grocery has a piece of French bread sticking out. Is this all we need to know (or care to know) about the French? The tower and the bread. Why not add accordion music and complete the stereotype? Now back to the movie. Will returns, only this time he wants to learn the true story about his father’s life because he has felt let down by a lifetime of tall tales and long absences.

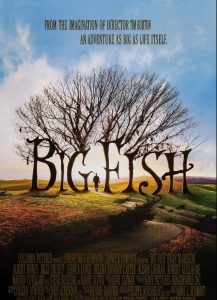

So, there it is. Edward tells his family (and us) the story of his life, which isn’t at all interesting, but is made that much worse by the forced sentiment and assumption that we are witnessing miracles of imagination. Director Tim Burton has, in my mind, made only one good film (1994’s Ed Wood) and after his latest, I can see why I find him so excruciating. In sum, Burton, like the character of Edward, is quite content to entertain himself, but he seems to have no regard for his audience. I am sure Burton had a great time constructing sets, encouraging his actors to chew healthy amounts of scenery, and not be bound by the limits of reality. Therefore, he can give us giants, witches with glass eyes that predict the future, two-headed Japanese lounge singers, and mythical fish big enough to swallow young children. Burton allows that these creatures are in the mind of Edward, but by the end we are meant to take them seriously at least partially, as Will comes around to Edward’s way of thinking and constructs one last story for the dying man.

But before we get to that final “fish story,” we must suffer through Edward’s egomaniacal rants that are, it is assumed, supposed to be cute and charming. He bullies his listeners (and us) into accepting his demented worldview, when the only proper label for this man is that of a congenital liar. Edward’s journey through life, as he tells it, is strikingly similar to Forrest Gump’s, as it is full of wartime heroics, small town eccentrics, and blind love for a vapid woman. Edward’s love story is arguably the most repulsive of the lot, as he falls in love at first sight, announces that will marry this woman even before speaking one word to her, and keeps her in his mind for three years until he can find her again. After he tracks her down at college, he shows up at her door and proposes marriage (again, he has never said one word to the woman). The woman, Sandra (played by Alison Lohman and Jessica Lange), tells him that she is already engaged, which prompts the self-absorbed ass-fucker to increase his obsessive behavior. He buys her thousands of flowers, hires a sky writer, and shouts at her window that he will indeed marry her. Some of the less sophisticated members of the audience might find this stalker-like behavior romantic, but as it was yet another example of Edward’s puffed up vanity, I couldn’t help but vomit throughout. This isn’t an old softie we are watching here, but a man so self-obsessed that he will not accept rejection. Everyone and everything must be caught, stripped, and placed in his ever-expanding trophy case.

Another example of Edward’s ego occurs when Will’s wife is discussing her recently published photos at the dinner table. Rather than ask the young woman to elaborate (after all, this is Newsweek, not some obscure lefty rag), Edward uses this as a springboard to bore the family further with another tale that they have heard hundreds of times. Edward simply cannot listen to someone else talk for more than five seconds without having to add his own bullshit. Fuck that, he can’t listen at all. A life force this big and this self-important does not have time for other people and simply tunes out if other egos intrude on his party. It is conceivable to spend a lifetime with this man (as Will realizes until he caves in like a pussy near the end of the film) without getting to know the real person, or having him know the real you. He will talk over you, through you, and without regard for other opinions until he literally beats you into submission. Since he reminded me of my grandmother, I wanted to kill the fucker. And I have no doubt that other viewers will find a point of reference as well, as we all know a relative who believes the dinner doesn’t truly begin until he or she enters the goddamn room.

Why Edward is like this we never know, although I must assume that he is mentally ill. Was he so disgusted with his life that he had to invent fanciful details to make it more bearable? Was he beaten and molested as a young man, which helped create multiple personalities? Burton isn’t telling. Still, without evidence, I must conclude that what we see is what we get and this old man either lived as he said, or is just one of those people who likes to add color to life and is merely a harmless clown. But the “people person” — the back-slapper and the hand-shaker — is not at all harmless, for at bottom, what he really wants is absolute control. He wants to be talked about when he’s not around, and whenever he arrives, he wants to be the first person consulted. By intruding on the lives of everyone and talking without interruption, he doesn’t want others to forget that without him, their lives just wouldn’t be as spirited. For Edward, to become indispensable (and perhaps cheat death, as all narcissists have a sneaking suspicion that they will never die) is to dictate how he is remembered and without differing interpretations. Perhaps that is why the old fart lies his ass off — facts would pin him down and force him to come to terms with what a cocksucker he is when the crowd goes home.

It strikes me that yes, it is possible to like this film, but only if you like Edward Bloom. If he reminds you of that slightly kooky uncle you haven’t seen in years, then maybe you should give it a shot. But I hate most of my relatives, living and dead, and I’m not about to endorse the sort of behavior that would cause me to leave the room, simply because it takes place in a movie. My sympathy was with poor Will, who never knew his father because the man was too busy constructing an image to distract us from the real prick beneath the lies. And my hatred also extended to Edward’s wife Sandra, as her only lines consist of enabling Edward to be such a bastard. Apparently, it doesn’t bother her that Edward hasn’t uttered one word that wasn’t in service of cock-eyed fantasy, so she must be loathed as well. Besides, Burton doesn’t develop her to any real extent, leaving us wondering why in the hell she’s so sad to see him go. For me, his death would be the one opportunity to tell it as it really happened, without fear of elaboration or contradiction. “Edward Bloom, fat lying SOB, died horribly last night of a massive stroke, screaming in terror for his pathetic life to continue, only to watch it ebb away in pain, loneliness, and bitter regret. He died as he lived; full of shit.” Now throw the fucker in the ground and let’s have a real party.