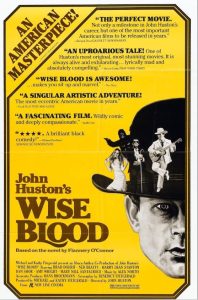

In any honest film that centers upon religious belief systems as a general theme, then delusion is required to be a secondary theme. Being based on a Flannery O’Connor novel, however, Wise Blood goes that extra mile and is populated entirely by people who are coprophagically insane. There is not a single redeeming character within, which makes sense taking place in the rural deep south. No two individuals have conversations with each other, talking past people and through them, babbling on with internal discussions that would sound more reassuring coming from the other side of the locked door of a padded room.

I hated every single character in the film and began to consider the value of prayer, as it would be the only practical way to initiate a rain of napalm upon every square inch of soil south of the Mason-Dixon line. As directed by John Huston, who clearly hates southerners with the fury of a tempest, it is a bleakly depressing film that breaks down religion into its component parts of desperation, ignorance, and revenue with machine-like precision.

At the helm is the perfectly-cast Brad Dourif, as a wild-eyed fanatic who fancies the notion of knowing The Truth. Most of the characters either believe in God indifferently due to a lack of interest or information about an alternative, or believes that God can be a great source of income. Hazel Motes (Dourif) truly believes in God, and his messenger Jesus, but he has come to the conclusion that Jesus is an asshole. The greatest ambassador that Jesus ever had was Hazel’s father, and as played by Huston himself, he brought the gospel that all of humanity sinned from birth and deserved a lifetime of pain and suffering before dying and receiving, well, more pain and suffering.

I believe Reverend Motes was intended to be Baptist, but he appeared more Catholic, as there is no religion more dependent upon self-loathing and ritualized sadomasochism. Hazel is plagued by daydreams in flashback where his father frightened him to the point of pissing himself, and instilled a strong belief that experiencing pleasure was the most vile crime imaginable. And so Hazel Motes returns to his home state to preach his own evangel, for his newly founded Church Without Christ, “Where the blind can’t see, the lame don’t walk, and the dead stay that way.”

He is surrounded at all times by signs imploring the populace that “Jesus Saves” and so he understands that his mission is a difficult one. His pulpit is a dusty Buick, and despite being as riddled with holes as his theology, it is a mighty chariot. As he intones to any garage mechanic who dares insult his whip, “No man with a good car needs to be justified!” The film would be amusingly quotable if it were not so mired in hateful characters.

Competing with his testament are an army of con-artist ministers (it is debatable as to whether there is another kind). One is played with guffawing vigor by Ned Beatty, and before Hazel can get a few words out, he takes over with aplomb, praising this prophet to the heavens while collecting dollars from the gullible crowd that has gathered around the Buick. This is an essential part of the southern economy, made up of the hustlers who know they are full of shit, and the vacuous flock who would like to forget they are full of shit. They give up their meager earnings for being convinced that life is not meaningless after all, and the ministers can stay flush with hookers. Everyone is happy.

Like any O’Connor story, it is brimming with southern-fried twits who are not as much ‘eccentric’ as they are ‘fucked in the head’. A boy who must be retarded as well as pathologically lonely attempts to help Hazel by stealing a mummified body for his use as a new Jesus, then thefts a gorilla suit to shake hands with the masses. A Lolita-type girl tries to seduce Hazel whilst regaling him with creepy stories from her adolescence, although being from the rural south, probably has never known a story that wasn’t deeply revolting. Her father is another hype minister who pretends to have blinded himself with quicklime, making him a more effective beggar, I suppose. Even the authority figures are missing several crucial bolts upstairs; a sheriff pulls over our protagonist, and rather than issuing a ticket, proceeds to push his car into a pond. Well, why not.

Though not entertaining in the traditional sense, Wise Blood shows the cunning craft of Huston, who sets up the world within the film only to knock it down. The images are unforgettable and visceral, from Huston’s own vile preacher to the sight of barbed wire wrapped around Dourif’s body. There is more often than not religious text written on a wall somewhere in the background, lacking in proper grammar and correctly spelled words, but always promising judgment on behalf of the God who both loves and hates you always. Dourif must be either coked up or diseased with mania, because he perpetually has the look of a man prepared to chew nails as he makes his mind known.

Hazel Motes may style himself as a vessel of Truth, but he has never fully escaped his self-disgust. While belting out the words to apathetic followers that Jesus is not needed to survive, he knows that it is only a matter of time before his resolve weakens and the Jesus pounded into his brain during those formative years returns to collect his soul. And so he is held in thrall, the one man with integrity in a melange of barely-human mental midgets awash in gleeful insanity.

And so he becomes Jesus when his Church Without Christ crashes down around him – at least he does not attempt to be one of the blind leading the blind. Within the grip of religion, if one truly believes, rather than simply humoring the traditions of religion in a harmless fashion, then one must live without hope, looking forward to basking in hellfire as punishment for having lived a life devoid of enlightenment. Maybe Jesus had a point in advocating such harsh comeuppance, though he was dead wrong on the reasons for it.