“Find some cause” -Narrator Fight Club

In the context of an individual entity like a human, there is nothing inherently objective when it comes to the idea of purpose. Having an awareness of this can certainly seem like a positive thing given how much individual freedom it grants a person, as opposed to something more objectively finite at birth. At the same time though, it’s important to recognize the reverse side of this revelation and how it essentially paints a portrait of anxiety that has essentially defined the whole of a society that is often overwhelmed by the burden of having too many options; so much so that it essentially makes the embrace of self-destructive/nihilistic impulses more apparent and even normalized rather than confusing.

Those with enough self-awareness pertaining to this reality can either become very depressed or merely immensely cynical when it comes to their confrontation with life. Fight Club can’t necessarily make the case for free will given how much so many of the decisions we make in our lives are based on circumstantial matters. Matters that have occurred while equally predating our existence or merely just the occurrence of the momentary reaction prompted by them.

However, the idea and ambiguity pertaining to the concept of free will has very much permeated the intellectual rigor of our culture. So much so that it has gravitated towards accepting the idea that despite the idea of free will merely being an idea, although it still refrains anyone from denying that we as individuals still have the freedom to choose how we respond to the things that happen to us.

In the case of the nameless narrator—who for the sake of honoring the newly adopted Fight Club analysis tradition of calling him Jack (Edward Norton)…He loses everything or at least every material possession he associated with the identity that he convinced himself was real and a means of self-determination. This leaves him both hollowed out and perpetually empty for a period of time.

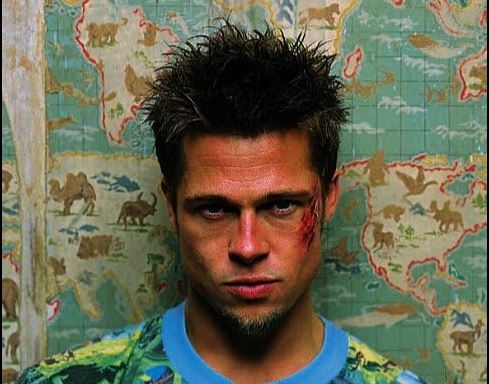

It’s like the prolific and charismatic Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt) said, “ “The things you own, end up owning you,” which couldn’t be a greater stab to the cancerous tumor we now recognize as consumerism. Now, owning something or even wanting a material possession isn’t necessarily bad. However, when a culture as fixated on material consumption as that of the West is, it almost devolves into the kind of epidemic that we don’t address.Instead, we find new ways of supplementing, as if that were to give us meaning and clarity rather than just adding more blindness to the very slavery that defines our system.

All this rhetoric and criticism of capitalism are what have painted Tyler Durden as a modicum of individualism for male fans of Fight Club to model themselves after. Granted, when looking more closely at the film and the way it analyzes the religious nature of the Fight Club and Project Mayhem phenomena, it only delves into more complex territory when deconstructing how misread the film is in terms of its true meaning.

“You’re not your job. You’re not how much money you have in the bank. You’re not the car you drive. You’re not the contents of your wallet. You’re not your fucking khakis. You’re the all-singing, all-dancing crap of the world.” -Tyler Durden Fight Club

As insightful and honest as this remark is, it can still be very easy for anyone who agrees with Tyler’s critique of the capitalistic model that has led to so much sociological self-destruction that it essentially breeds a new form of collective religiosity. This is in opposition to the rugged individualism that his anti-consumerist rhetoric espouses. All this goes back to Fight Club, and although it provides an avenue for treating the very repression most men face in today’s world given that a lot of it has been defined by the confirmative social model.

This is where it is more important to get a steady paying job from a corporate entity, forming a family, and essentially complying with the rules of a debt-ridden economic system that perpetuates happiness, respectability, professionalism, and even individuality (LOLFL). All you have is another trade-off rather than an actual solution.

As much badassery can be attributed to the rules of Fight Club; “The first rule of Fight Club is: you do not talk about Fight Club. The second rule of Fight Club is: you do not talk about Fight Club! Third rule of Fight Club: someone yells stop, goes limp, taps out, the fight is over. Fourth rule: only two guys to fight. Fifth rule: one fight at a time, fellas. Sixth rule: no shirts, no shoes. Seventh rule: fights will go on as long as they have to. And the eighth and final rule: if this is your first night at Fight Club, you have to fight.”

The charismatically delivered rhetoric of Tyler is really no different than the thematic flare a hyper-energetic preacher or motivational influencer has on a mass audience. These have either bought into the subtly depicted sales pitch, or have essentially convinced themselves that they have found “The Answer”.

This answer is a reflection or whatever a person believes will be the solution to the many problems that perpetuate and define their life as an individual. Then again, one of the more brilliant things about Fight Club is that along with its critique of both capitalism and the dangers of adhering to any counter-revolutionary narratives of rebellion (which can all take on an extreme of their own), is that it essentially presents the question as to what is individualism in our modern age.

On a basic level, the term individualism is defined as “the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual”. That outlook can be attributed to a character as brash and independently thinking as Tyler Durden. However, even though several of the key points he makes do have a sense of clarity and accuracy, they hardly detract from the more contradictory nature of his collectivist views where he pretty much compartmentalizes every member of Fight Club/Project Mayhem. “You are not special. You are not a beautiful or unique snowflake. You’re the same decaying organic matter as everything else.”

From a purely biological level, Tyler is correct to point out what human beings are made of. But given the self-importance human beings attribute to their individual personas, the prior remark essentially invalidates the individualism he espouses as part of his anti-capitalist/anti-consumerist views. Anyone who has seen Fight Club is familiar with its twist reveal of Tyler and Jack being the same person.

At the same time though, the fact that Tyler is an embodiment of everything the Jack’s subconscious wanted to be very much how many people often imagine a better version of themselves is itself an intriguing way of looking at the purpose of Fight Club and the intentions of writer Chuck Palahniuk who stated that “Fight Club” “was a lot of psychodrama and gestalt exercises that would empower each person. Then, ideally, each person would leave Fight Club and go on to live whatever their dream was—that they would have a sense of potential and ability they could carry into whatever it was they wanted to achieve in the world. It wasn’t about perpetuating Fight Club itself.’“

Aside from the reactionary effect Fight Club has had in inspiring the formation of multiple real-life Fight Clubs across the United States, the fact that Tyler Durden’s popularity has operated as a form of radicalized individualism is itself a deeper statement in regards to the nature of the very psychological frustrations explored both in the novel and the film. These mentioned frustrations pertaining to masculinity, a dissatisfactory work culture, and the consumerism that acts as a comfort apparatus are essentially the factors in that author Chuck Palahniuk tackles.

In a 2021 Joe Rogan podcast interview, Palahniuk discussed how he enjoys making people uncomfortable through his work. Although this remark can be centered on a sadistic or malevolent urge,it’s much more intellectually honest in analyzing the deeper discussion at hand when looking beyond the author’s intention of creating a level of discomfort for the person.

This works more as a form of deconstruction with the sole purpose of tearing down the individual and essentially helping them rebuild themselves with the much-needed essentials. In many ways, this act resembles the very trials and tribulations that Jack experiences when losing the apartment, he had filled with so many of the very superficial material possessions he deluded himself into thinking would complete him. However, as Tyler Durden said, “Only after disaster can we be resurrected. It’s only after you’ve lost everything that you’re free to do anything. Nothing is static, everything is evolving, everything is falling apart.”

When looking at the culture of conformity and over-indulged comfort that the quasi-religious impulse of consumerism has generated, it only unravels a truly horrifying reality regarding the degeneration of a multitude of generations. These generations have become more subservient to any institutionally promoted mode of complacent conformity, or a more generally crafted form of mediocrity that essentially crushes any sense of identity or even spiritual fulfillment. It would be relatively easy to see the impact and phenomenon of the fight club depicted in the film as an avenue for the kind of toxic masculinity that often paints men as either abusers or much more susceptible to violent power grabbing.

However, by looking closely at the fights that take place within the fight club and the narrator’s observance, the release the men in the fight club receive from their participation in the fights serves as the kind of release that carries an almost sexual but equally spiritual fulfillment that modern life failed to provide for them. If anything, the purpose that Fight Club serves for its members is that of a spiritual fulfillment that their professions, their consumerist vices, and even their false notions of masculinity in a de masculinized culture have failed to deliver.

Fight Club isn’t presented as the answer so much as an indicator as to what men in our modern generation are currently seeking as opposed to filling the void formed through the overabundance our modernity has provided. As much as several groups be it social justice warriors or any organizations that champion minority groups undergoing a particular form of systematic oppression argue about how unfair life is, on a basic level, things have essentially become much easier from an industrial and technological level.

However, despite how someone like Steven Pinker will argue that things have gotten better, the downside of this evolutionary component has led to an overabundance of many commodities, be it food or comfort that has essentially eliminated the spiritual essence that gave people a sense of meaning. This could also be the overall wholeness that comes with being part of something bigger than yourself, or even working hard for something that truly lasts for a moment of what we can often interpret as perfection..

Narrator: When people think you’re dying, they really, really listen to you, instead of just… Marla Singer: instead of just waiting for their turn to speak?

Jack suffers from insomnia, and after countless attempts to cure it, he eventually stumbles upon the solace he derives from frequenting support groups. This discovery essentially turns from a spiritual cure to that of an unnerving addiction where these various support groups he frequents; be it men suffering from testicular cancer, melanoma, or some depressive disorder.

These only highlight the spiritual emptiness that defines him and the blindness that characterized the materialistic consumption that defines many consumers in the United States. In Jack’s case, his consummatory habits essentially failed him to a point where he saw no other option than to seek out some form of unconventional human connection, even if it meant “I let go. Lost in oblivion. Dark and silent and complete. I found freedom. Losing all hope was freedom.”

It is this admittance of a loss of hope that gives Jack a sense of peace, and although it started with the support groups, it only becomes more apparent in his formation of Fight Club, and how it provides the same function for the many spiritually disposed members who join it. Sadly, these same men who find a sense of fulfillment in discovering the liberation that gives Fight Club its hyper-individualistic release ultimately fall prey to the more collectively oppressive mindset that defines the pseudo-anarchic mantra of its evolution into the terrorist-oriented approach Project Mayhem fully embraces.

Project Mayhem’s supposedly noble intention was to destroy the same economic-financial system that for decades has not only crippled the middle class across the United States with excessive money printing, debt expansion, and ridiculous taxation. This system also created the very avenues of the same emptiness that creates this highly materialistic/status-based culture.

A culture that has done nothing but further create the same cultural disparity Tyler Durden believes is a spiritual war that nobody with proposed solutions ever tries to win so much as put a band aid on. The absurdity of these patterns is replicated within the mentality of the Project Mayhem members, who pretty much forfeit the very individualism that they were convinced Fight Club offered in its genesis.

As a narrative, Fight Club is many things. It’s dark, violent, graphic, self-explorative, and outright f-ing hilarious when it comes to its twisted overview of all the flaws that pervade and characterize a highly socialized culture we treat as if it was normal or sane. But in its ability to use a character as charismatic and yet equally terrifying as Tyler Durden, in contrast to the often hopelessly empty Narrator (Jack) and even the nihilistically comical Marla Singer (Helen Boham Carter).

It also manages to challenge many of the social and societal norms that have been forced on individuals and to an extent. Instead of being complacent, they confront them through the kind of self-examination that only gives more weight to Tyler’s line “How much can you know about yourself? You’ve never been in a fight. I don’t wanna die without any scars. So come on; hit me before I lose my nerve.”

“There are times when those eyes inside your brain stare back at you.” – Charles Bukowski

Leave a Reply