Over forty years after it was first released, Martin Ritt’s not only hasn’t aged a bit, it has actually grown in stature; a product of a more mature Hollywood that knew it could get away with cynical, downbeat character studies because there were audiences ready to receive them. Paul Newman’s Hud Bannon — amoral, vain, and hard as death itself — is a portrait of the emerging American man; removed from the sacrifices of war, and fully committed to the idea that values, rules, and society itself must yield to the naked ambition of a new generation. But Hud’s no go-getter. He simply wants Homer, his aging, righteous father (played by the flawless Melvyn Douglas) to surrender his beloved ranch to the oil business or, frankly, get out of the way — voluntarily, or by taking that long-awaited dirt nap. And Hud is far too busy bedding the small Texas town’s married ladies (or flirting with the family housekeeper, Alma, played by Oscar-winner Patricia Neal, with that delicious combination of plainness and sweaty eroticism) to really put his mind to anything productive, even if he has plans that proudly neglect family loyalty, love, or being a responsible role model to his nephew Lonnie (Brandon de Wilde). He’s a bastard through and through, but Newman’s portrait is so compelling that even I wanted to see what was inside those jeans. James Wong Howe’s black-and-white cinematography is as good as you’ll find anywhere, with the dusty, lonely streets and endless prairies speaking to the essential loneliness of Hud’s existence. Amidst the social commentary and Lear-ish overtones, there’s also a striking allusion to the Holocaust, less than twenty years removed from the film. After a deadly disease is discovered among Homer’s cattle, they are rounded up, stuffed in a pit, and shot one by one with gruesome efficiency. The slaughter not only signals the beginning of the end for Homer (what’s left without the daily ride over his land?), but it also marks the end of hope for men of his character. A way of life, once tied to one’s very identity, is now mere business; pride, ownership, and a job well done surrendered with little resistance. Still, this is far from a reactionary pining for days of yore. As rotten as Hud is, he never fails to be the most attractive human being in any given scene. More than that, he’s the only man present who speaks openly and honestly about life’s fleeting joys, and how in the end, nobody gets out of life alive. The venomous words he throws at Lonnie near the conclusion may sound heartless, but they’re no more so for being true: This world is so full of crap, a man’s gonna get into it sooner or later whether he’s careful or not. Or consider his sound advice to his young charge earlier in the film: “You don’t look out for yourself, the only helping hand you’ll ever get is when they lower the box.” But a speech to his father before the cattle massacre speaks most pointedly to the film’s overarching theme: This country is run on epidemics, where you been? Price fixing, crooked TV shows, inflated expense accounts. How many honest men you know? Why you separate the saints from the sinners, you’re lucky to wind up with Abraham Lincoln. Now I want out of this spread what I put into it, and I say let us dip our bread into some of that gravy while it is still hot.” The film doesn’t flinch from its pessimism, for as we know, men like Hud now pull the strings. Certainly, they always have, only we’re comforted by the illusion that once, long ago, men like Hud remained in the shadows because the culture wouldn’t tolerate their self-serving tricks. Even Alma, like Homer a moral center of the film, can’t help but admit that in the face of Hud with his shirt off, she too had to stop what she was doing and put down her dishtowel. She leaves the ranch after Hud gets a bit too rough, but we can see the regret in her eyes. She would have slept with him eventually, it just had to be on her terms. And there’s no guarantee that she won’t be back. Even Lonnie might return in the end, once he discovers for himself that Uncle Hud — the son who never failed to disappoint dear old dad — was, depressingly, absolutely right. |

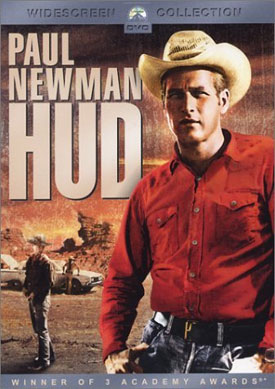

Hud (1963)

by

Tags:

Leave a Reply