Synopsis: “What about the old American social custom of self-defense? If the police don’t defend us, maybe we ought to do it ourselves.”

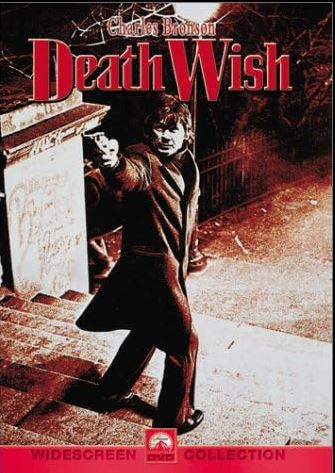

Director: Michael Winner

Cast: Charles Bronson, Steven Keats, Vincent Gardenia, Hope Lange

Bronson’s ascent to the top took the best part of two decades, peaking with the massive international success of his merciless turn as a mugger-eradicating slayer in Death Wish. Its mid-seventies audience couldn’t get enough of its anti-liberal, button-pushing controversy, thrilled by the sight of an ordinary man fighting back against the scourge of street crime. Everyone knows Death Wish, everyone knows what it’s about, and everyone knows Bronson’s in it. Like Anthony Perkins in Psycho, it was a role he never escaped.

However, its premise was established sixteen years earlier in the little-known Gang War. Here Bronson plays L.A. high school math teacher Alan Avery, a moral, unremarkable man with a heavily pregnant wife. Instead of urban scumballs stuffing up his quiet life, this ex-soldier has to deal with blundering gangsters after seeing the car park stabbing murder of a stoolie. His missus is none too happy about him agreeing to testify in court, warning that witnesses often get murdered, but Avery is determined to push ahead. “For two years in Korea there was a whole army on the other side trying to kill me,” he tells her, “and they didn’t come close.”

But once the newspapers get hold of the story, it isn’t long before a scarred, punch-drunk ex-boxer is sent to his home to ‘slap around’ his wife. From here on, all those plot points we’ve since come to love fall into place – domestic harmony obliterated, a justice system that bamboozles an honest man and favors the scuzzy perps, colluding cops, women having no fun at all, and an armed anti-hero forced to make a stand.

Gang War is a fast-moving, cheesily enjoyable seventy minutes, even if it lacks Bronson going on the rampage. It moves in for the kill and then blinks right at the death. Fast forward sixteen years and Death Wish was ready to push such a template much further.

Now I haven’t read Brian Garfield’s novel Death Wish but I do know it’s anti-vigilantism. Michael Winner, hardly the subtlest of directors, took that angle and gleefully flipped it. Was it the right thing to do? Of course. Only nitwits bang on about the validity of a movie’s message whereas I just crave entertainment. Winner’s bastardization of the source material was rewarded by Death Wish not only striking a controversial chord, but spawning a franchise.

One of the many things I like about this box-office monster and pop culture touchstone is its plausibility. It’s hard to attack any aspect of its setup during the first forty-five minutes. Bronson plays Paul Kersey, a happily married, middle-aged architect with a pretty daughter. He’s no foul-mouthed bigot on the edge like the titular antagonist in 1970’s Joe. This is a man who was a conscientious objector during the Korean War and remains anti-gun after his dad was killed in a hunting accident.

He’s even managed to hang onto some empathy, optimism and hope, despite living in New York City, a place variously described as a ‘war zone’, ‘goddamned city’ and ‘toilet’ with up to twenty-one murders a week. A rightwing colleague, who half-jokingly wants the underprivileged herded into concentration camps, labels Kersey a ‘bleeding heart liberal’ to which he replies: “My heart bleeds a little for the underprivileged, yes.”

Of course, everything begins to change when a savage home invasion sees Kersey’s wife killed and his sexually assaulted daughter left catatonic. This unsettling sequence (especially the way it accelerates as a hyperactive, greasy-haired Jeff Goldblum yells “Goddamn rich cunt! I kill rich cunts!”) is well done. Unusually for this kind of pic, Kersey is not instantaneously launched onto a one-man crusade. Instead, he continues to be aware of the crime all around him before an encounter with a would-be mugger leaves him shaken by his own use of non-lethal violence.

Things gather pace during a working trip to Tucson, Arizona to meet a gun-loving client. “Unlike your city, we can walk our streets and through our parks at night and feel safe,” Kersey is told. “Muggers operating out here, they just plain get their asses blown off.”

Kersey still doesn’t harbor any plans to become a vigilante, the narrative showing that but for some chance meetings he would’ve just shuffled off into heartbroken loneliness. He doesn’t even sort out a gun himself. It’s almost as if fate is pushing him into becoming an avenger.

At key points, Bronson is very good. Never the most energetic of performers, his low-key, reticent turn serves the story well. When told by a doctor that his wife is dead we merely get a close-up of his trembling face, a clergyman’s words of solace laid over the top as the scene segues into a snowbound funeral. Boy, Bronson looks old and defeated as he trudges away. He’s even better when shooting his first mugger in the chest in a wintry park. There’s no joy, no thrill, no quip, the act leaving him unable to do anything but stare at the writhing man gargling on blood. It’s a robotic killing and Kersey reacts like he can’t believe what he’s just done.

Bronson gives a laconic but steely performance throughout. It is entirely lacking in histrionics and speeches, and perhaps its understated feel is one of the reasons that it has woven its way into movie lore. The lean, convincing and always relevant Death Wish, aided by Herbie Hancock’s effective score, also results in one of my favorite closing shots (up there with The Taking of Pelham 123) in which a newly relocated Kersey points his gun-fingers at a gesticulating gang of punks in a Chicago train station, concisely informing us that he’s never gonna stop.

Despite its runaway success, Death Wish did not propel Bronson into a series of quality flicks. Perhaps the best of the rest of the seventies was the average Hard Times in which he once again dusted off his Strong But Silent act by playing an aging bare-knuckle fighter. Once the 1980s rolled around Bronson disintegrated into all-out shit like Messenger of Death and Murphy’s Law, although you should still seek out the nudey madness of 10 to Midnight, the nasty Death Wish II and the cartoonish Death Wish 3.

Leave a Reply